Amble comet scientist: Fingers crossed for Philae lander

Amble born Professor Fred Taylor is Halley Professor of Physics (Emeritus) and has written many books on atmospheric physics and the planets of our solar system.

Professor Fred Taylor, who was born in Amble, is part of the Rosetta comet mission. Professor Taylor and his team are using equipment on board the Rosetta spacecraft, to analyise the structure of comet 67P.

Professor Taylor sent this exclusive report to The Ambler

The Rosetta Mission to a Comet

Rosetta had its origins in the 1980s, in the Alpine resort of St Moritz, where I was a member of a team of experts that had been invited by the European Space Agency to discuss the scientific priorities for future space missions.

After much debate, we recommended a project we called Comet Nucleus Sample Return, which would involve not only flying to a comet but landing, collecting samples, and bringing them back to Earth. This was deliberately ambitious, and eventually the sample return part had to be discarded because of the high cost, which even without sample return is well over a billion pounds.

Now, nearly 30 years later, we have Rosetta flying around Churyumov-Gerasimenko (usually called by its catalogue number 67P, for obvious reasons) and the small lander called Philae has just landed on the surface.

Analysing the structure of the comet

The role of the lad from Amble in the mission is as a member of the spectrometer team on the Rosetta orbiter, the large ‘mother ship’ that released the lander yesterday. Our team has about thirty members from several countries, including France, Germany and the USA, and is led by scientists from the National Institute for Astrophysics in Italy.

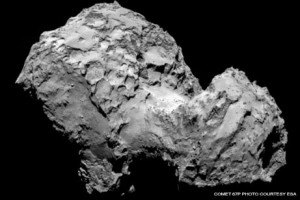

The nucleus of comet 67P, photographed from the Rosetta spacecraft from its orbit about 30 miles away. This, the solid part of the comet, is less than three miles across in the longest direction, but later, when it gets near the Sun, it will emit gas and form a bright coma and a tail many thousands of miles long. (Photo: ESA).

Together, we study the comet’s surface, and the gas it gives off when it gets near the Sun, by taking images at a wide range of visible and infrared wavelengths. By analysing these, we can find out what the comet is made of.

At the moment, 67P is still outside the orbit of Mars and is too cold to emit much gas, so since arrival in August we have been looking at rocks and ices of various kinds on the surface of this strangely-shaped object (see picture). The plan is to continue observing as we follow the comet on its orbit around the Sun and it develops the characteristic long, bright tail of gas and dust.

Rocks, ice and black tarry stuff

The little lander may not last that long, and as I write the day after landing there is a struggle going on at mission control in Germany to keep it upright on the rough, irregular surface so it can even begin to make its planned measurements.

Our spectrometer team is relying on it to help solve a puzzle: one of the things we are seeing on the surface, along with the expected rocks and ice, is some black tarry stuff that seems to be organic but is proving difficult to identify from spectroscopy alone.

If Philae can analyse some of this directly, using its on-board chemistry lab on the surface, it will help to pin down exactly what this material is. Our fingers will remain crossed for a while yet.

Professor FW Taylor

Halley Professor of Physics Emeritus

Fellow of Jesus College

University of Oxford

Related article: Stargazing fans: meet Amble’s own space man