The Great Longitude Prize

On 21 June 1773 a clockmaker from Yorkshire scooped what was then the biggest scientific prize in British history. His legacy continues to this day with his descendants, a local family who are continuing their ancestor’s entrepreneurial spirit.

In 1714 an Act of Parliament offered a £20,000 prize to anyone who could invent a way to accurately determine the exact position of ships at sea. There are two co-ordinates used in such a calculation; latitude, the distance north or south of the equator, and longitude, the distance east or west from an agreed point.

Using the sun at midday, or the Pole star at night, latitude was easier to determine, but longitude remained much harder to calculate. With maritime trade and exploration growing quickly, the toll on human life and loss of cargo was also increasing.

When 2000 men were lost at sea in 1707 alone, the British government were spurred on to act. The prize was announced and a Board of Longitude was set up to judge the submissions.

In those days, clocks used pendulums to drive the timekeeping mechanisms. Once at sea in the rocking high waves, the pendulums would quickly become inaccurate.

It was assumed by the Board that the solution would likely be found in calculation tables and formulae, rather than the invention of a new gadget.

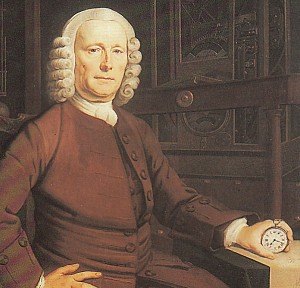

But John Harrison, a clockmaker from Yorkshire read about the prize and felt he could design an accurate and portable timekeeping device of his own invention.

It’s in the genes

The story of Harrison’s design and battle with the Board of Longitude is well documented in history books – suffice to say he was able to develop a watch mechanism which accurately solved the longitude problem.

It took him fifty years, and due to politics he was never officially awarded the actual ‘Longitude Prize’! Harrison had to go to the then King George III to demand his money.

Phil Derry, Commodore of Coquet Yacht Club (www.coquetyachtclub.co.uk) is a direct descendant of John Harrison. He and his son Simon continue the entrepreneurial lineage with their location company www.trackaphone.com.

Their technology enables them to pinpoint and track the exact location of any individual and asset across the globe.

Phil said “John Harrison was my (x6) great-grandfather on my mother’s side. From what I have read about him, I am sure my son has inherited his disposition. He has the same stubbornness and attitude towards quality and attention to detail.

“The £20,000 (today about £8 million) was left in Trust to all John Harrison’s children and then down the family line to enable each one to learn a trade. Many went to Australia and other parts of the world. The Trust fund ran out in the mid 1900’s.”

Harrison’s legacy still lives on in the area, and his story even spills out into popular culture.

“Since we have lived in Amble we have learnt that one of John Harrison’s descendants lived in Warkworth making clocks and there is a Harrison clock in the village,” said Phil.

He laughed; “The last episode of Only Fools and Horses tells the mythical tale of Del Boy finding Harrison’s lost chronometer and “making it at last”!

The 2014 Longitude Prize

A modern day Longitude Prize was recently announced, and members of the public were asked to vote on who should be chosen for a £10million investment. Six categories were identified: flight, paralysis, water, antibiotics, food and dementia.

Phil said “I think this is a great idea and my favourite would be dementia because at TrackaPhone we often tackle dementia projects using our location technology to look after people”.

To read more about the categories and cast your vote, visit www.longitudeprize.org. Voting ends on 25 June.

Anna Williams